Mitcham's Corner Development Framework SPD

3. THE GYRATORY: a vision for change

3.1. Introduction

Purpose

3.1.1. This chapter presents a vision for change to the existing movement framework within the Opportunity Area, by setting out high level principles for the remodelling of the existing gyratory system and aspirations for potential public realm improvements within the area.

(3) 3.1.2. The preferred movement option shown on page 33 seeks to better balance the needs of all road users and create the right conditions to promote a positive sense of place. It represents an option for achieving the vision and objectives for the Development Framework by removing barriers to movement, unlocking land for positive development and the creation of a new public open space.

(1) 3.1.3. Overall, the chapter promotes a placemaking approach to streetscape design; the benefits of creating a sense of place are summarised in the adjacent image (figure 19). It advocates that by making the area more enjoyable, safer, easier to get to and move around, these improvements would be good for local businesses and may help to attract investment within the area.

Figure 19: The benefits of creating place

A shift in street design & addressing the issue of speed

(1) 3.1.4. A shift in attitude towards street design and management is taking place. The Manual for Streets by the Department of Transport was an important step in 2007 and then was followed in 2010 by Manual for Streets 2, which extended the principles to cover all roads except trunk roads.

3.1.5. Through these documents the government has recognised the importance of low speed in creating safe, sociable and attractive streets. Both documents stress the importance of streets not only as conduits for movement but as places to visit and spend time. Furthermore, Manual for Streets 2 outlines and provides evidence for the benefits of better streets including: increased economic vitality, improved noise and air quality, and an increase in sustainable travel choices.

3.1.6. The aspirations and key development principles set out within this chapter are consistent with those set out in Manual for Streets 1 & 2.

3.2.Current problems

(2) 3.2.1.Mitcham’s Corner is a vehicle dominated space, which prioritises motorised vehicle use above that of pedestrians and cyclists. As a result, the gyratory has a negative effect on the identity and physical environment of Mitcham’s Corner.

(2) 3.2.2.The current traffic arrangement consists of a two-three lane, one way gyratory system introduced in the late 1960s. The resulting layout includes five junctions, three of which are signal controlled in addition to puffin and zebra crossings. Stop-vehicle movements patterns and one way flows creates perceptions of high traffic speeds.

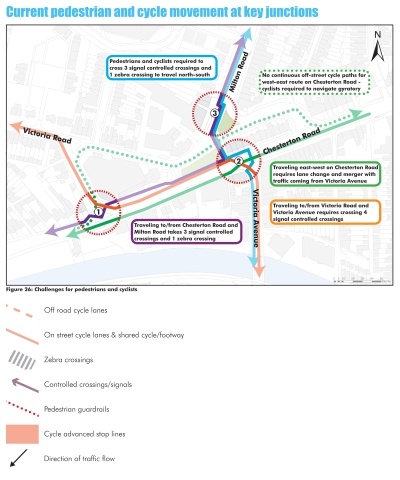

(3) 3.2.3.For pedestrians and cyclists, the confusion of routes (see Figures 26a and 26b) is compounded by the complex crossing arrangements. Pedestrian footways are very narrow in a number of places, which is exacerbated by the need for a shared-contra-flow cycle provision along several lengths.

3.2.4.The gyratory and associated increased vehicle movement have come to dominate, fragment and erode the character of the area. Large areas of underused space are evident and there is a notable absence of any clear, identifiable sense of place.

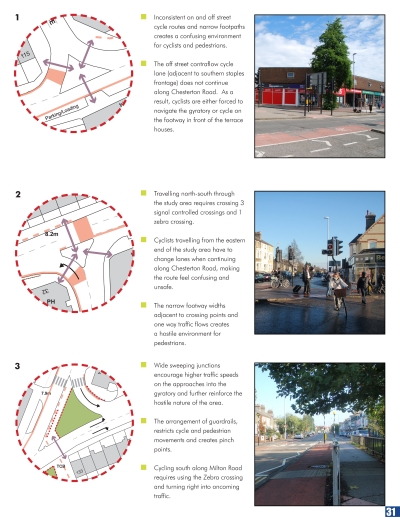

(7) 3.2.5.The current problems are summarised below:

- Confusing environment for drivers, cyclists and pedestrians; extensive on-way flows, lane changes and complex crossing arrangements;

- Fragmented nature limits the accessibility of the area and increases journey times and distances for pedestrians and cyclists;

- The gyratory forms a barrier to movement and severs surrounding communities;

- Traffic volume and street ‘clutter’ has diminished the quality of the streets. It is an unpleasant cycling and walking environment;

- Lack of regard to pedestrian desire lines as crossings; key destinations and streets are poorly connected;

- Fragmented and incoherent retail provision. The Co-operative is physically and perceptually isolated from the small shops and businesses on the south side, which in turn have no connection with the retail provision at the south-east end of Milton Road;

- Large areas of underused space. An isolated and deserted raised green space adjacent to Lloyds Bank severs the area and interferes with pedestrian/cycle desire lines;

- A lack of destination or places to stop and rest, contemplate or ‘watch the world go by’;

- A general lack of quality in streetscape creates a poor northern gateway to the City Centre.

Figures 20 to 25: Views from the gyratory

(4) Figure 26: Challenges for pedestrians and cyclists

3.3. A solution...Severing the gyratory & creating a low speed environment

(1) 3.3.1. The radical transformation of the gyratory system is identified as a key public realm and infrastructure project within Policy 21: Mitcham’s Corner Opportunity Area.

(7) 3.3.2. The severing of the gyratory system to create opportunities for public realm improvements are considered fundamental to achieving the vision of “maintaining the vibrancy of the local centre, improving connectivity between people and places and to reinforce a strong local character and identity” (emerging Local Plan, supporting text Para 3.89).

(1) 3.3.3. A County Council and City Council officer/consultant workshop was held in February 2016 to consider the best options for changing the highway configuration of the junction. From this process two favoured options emerged which are currently subject to traffic modelling work by the County Council to assess the likely impacts. A note of the workshop is available as a background document.

(3) 3.3.4. Key to creating space for streetscape improvements is the adoption of a low speed highway design, as this is considered the most critical measure to restoring the balance between people and vehicles. Adopting a low speed design could manage the impact on traffic delays and queues.

3.3.5. The application of standard highway solutions, is increasingly coming under question and a number of established precedents do exist in the UK which have replaced conventional street and junction design by simpler and more integrated solutions.

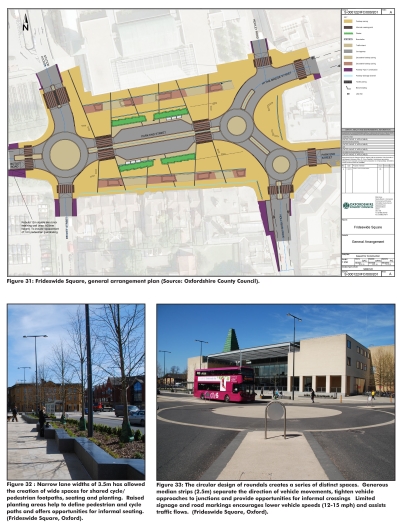

(2) 3.3.6. A recently completed major junction improvement in Oxford which is similar in nature to Mitcham’s Corner, was redesigned to create an integrated low speed environment. A general arrangement plan and photos of the scheme can be found on page 37.

3.3.7. Early feedback on the scheme in Frideswide Square, Oxford suggests that traffic delays have reduced despite a reduction in overall carriageway space, which has facilitated significant public realm improvements in the square. This scheme accommodates around 37,000 daily movements as well as very large volumes of bicycles and pedestrians from the adjoining railway station.

3.3.8. Whilst every street is unique and the context of Mitcham’s Corner is different, existing precedents are helpful in exploring options and generating ideas for improving the public realm within the Opportunity Area.

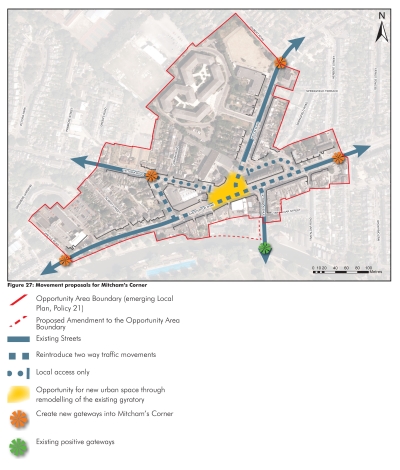

(2) 3.3.9. A preferred officer option for remodelling and severing the gyratory system is illustrated in figure 27.

(30) Figure 27: Movement proposals for Mitcham's Corner

Relationship with The Greater Cambridge City Deal

3.3.10. The Greater Cambridge City Deal is an agreement set up between a partnership of local organisations and Central Government, to help secure future economic growth and quality of life in the Greater Cambridge city region. It is the largest of several City Deal programmes taking place in the UK

3.3.11. The City Deal programme is based on the Transport Strategy for Cambridge and South Cambridgeshire and supports the emerging Local Plan.

(2) 3.3.12. The City Deal scheme for Milton Road is part of tranche 1 of the City Deal and seeks to integrate transport improvements along the corridor. Whilst existing gyratory system is not part of this scheme, there is potential for it to be included in future tranches of the City Deal programme.

(1) 3.3.13. Mitcham’s Corner is at a pivotal location in the transport network and improvements to how it currently functions could greatly help both increase and improve the use of more sustainable modes of travel in Cambridge. It is considered that the proposed changes to Mitcham’s Corner as set out herein are fully compliant with the agreed objectives for City Deal.

(1) 3.3.14. The delivery of improvements to the gyratory at the scale set out in this Development Framework will more than likely require a phased approach to delivery. This means that it could be possible, or even preferable, to stage the works across different months/years such that it is both practical and keeps the network moving in the meantime as well as achievable financially.

(3) 3.3.15. For example, subject to further modelling and agreed design speeds/capacity on this part of the network, the works could include :1) reversion of the one-way system and removal & re-modelling of existing junctions only; 2) delivery of the majority of landscape and public realm improvements; and finally 3) creation & assignment of areas for cycle and car parking, public use, street furniture, etc.

3.4. Moving forward...Key objectives for remodelling the gyratory

3.4.1. It is likely that the revitalisation of Mitcham’s Corner will take place over many years. Collectively the aspirations set out within this chapter represent a longer-term vision.

(12) 3.4.2. It is essential that any potential options for the remodelling of the gyratory system should successfully combine efficient traffic movements with the broader placemaking objectives for Mitcham’s Corner to:

- Maintain sufficient capacity and flows through and around the area;

- Maintain and improve access and connectivity to residential and business areas;

- Enhance the spatial quality of the public realm to promote investment;

- Improve safety and comfort for all modes, especially pedestrians, cyclists and those with disabilities;

- Provide opportunities for business expansion and development;

- Create a more coherent, permeable and distinctive district centre, with well located bus stops as a key element.

3.5. Key design principles

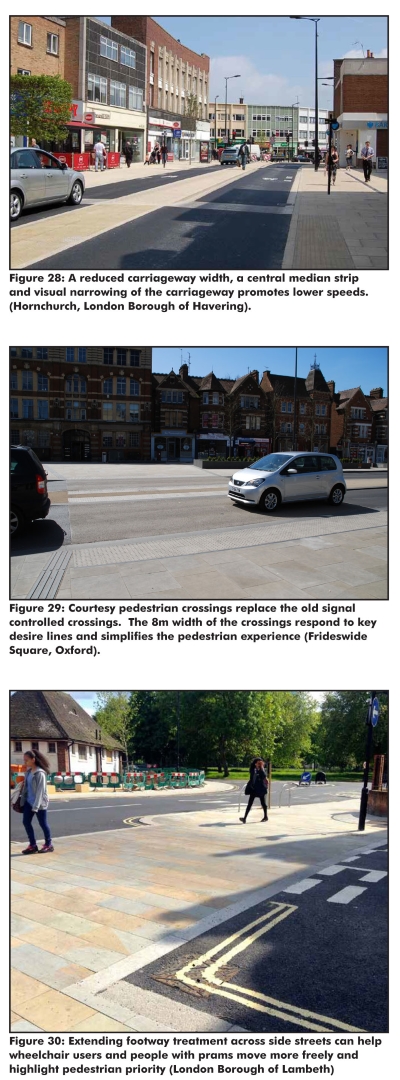

(12) 3.5.1. Any future potential options for remodelling the gyratory must successfully combine traffic and streetscape arrangements. A number of key design elements are identified below which have been successfully designed in other urban areas with similar challenges. These are consistent with Manual for Streets 1 & 2, in addition to the emerging Local Plan Policy 21, and should therefore be incorporated within any future option for the remodelling of the gyratory. Precedent images can be found on pages 36-37(“Figures 28 to 30: Transport examples” and “Figures 31 to 33: Transport examples”).

- Create a low-speed environment of between 15-21mph;

- Create clear gateways and transition points into Mitcham’s Corner;

- Keep carriageway widths to a minimum and employ visual narrowing;

- Reintroduce two way flows;

- Minimal signage and road markings.

(2) 3.5.2. The creation of a low-speed environment is central to creating a better balance between people and vehicles and should service as the starting point. Design speed should not be confused with speed limits.

(1) 3.5.3. Carriageway widths, turning geometries, sight-lines, crossing arrangements and junction controls are all determined by design speeds. For example, the lower the design speed, the tighter turning angles can be at corners making motor vehicles approach a junction with more caution and slow down. Tighter corner radii also results in shorter crossing distances and responds better to pedestrian desire lines.

(3) 3.5.4. Design speeds of between 15-21mph are the most effective in achieving the most efficient and safe use of streets in complex urban areas.

3.5.5. Achieving the appropriate design speed depends upon establishing clearly defined transition points between the higher speed, more segregated highway, and the lower speed, more integrated context that is promoted for the Opportunity Area

3.5.6. Distinctive transition points can help modify driver expectation and speeds close the boundary of Mitcham’s Corner.

3.5.7. A number of potential transition points (gateways) have been identified on figure 27 and these should be emphasised in any detailed design proposal.

Reduced carriageway widths - physical and visual

(4) 3.5.8. Drivers slow down when they feel the space they are travelling through is narrow. Activity at the side of the street is closer to the carriageway, more visible and more likely to encroach onto the carriageway, meaning that motorists may reduce their speed.

3.5.9. Reduced carriageway widths are also essential in maximising opportunities for pedestrian and cycle crossings, and minimising the interference of these crossing with traffic flows.

3.5.10. Extensive one way systems are rarely compatible with lower speed environments and do not create legible environments.

(3) 3.5.11. Any detailed design proposal for Mitcham’s Corner should seek ways to return to two-way traffic flows. None of the principal streets in the Opportunity Area are too narrow for two-way traffic flows.

Other elements that promote low speeds

(4) 3.5.12. There are a number of other elements that promote slower speeds and greater integration of traffic with pedestrian and cycle movement. These include:

- Visual narrowing - reducing the apparent width of carriageways. For example the space next to the kerb (the traditional gutter area) can be of a different material/colour to the carriageway to make the carriageway appear narrower. Although this feature is flush and drivable, it appears as part of the footway/kerb edge.

- Signs and lines - Highway elements such as road markings and excessive signs are rarely compatible with placemaking, and should therefore be reduced wherever possible. The starting point should be “design with nothing and then add only what is necessary” (Manual for Streets 2). Minimal signage and road markings make the carriageway feel like it is not designed solely for motor vehicles and encourage drivers to be more aware of their surroundings.

(2) Figures 28 to 30: Transport measures

(7) Figures 31 to 33: Transport examples

3.6. Promoting place - Rediscovering the mixed use high street

(1) 3.6.1. The change in road layout and street design promoted within this chapter supports the aspirations of the Local Plan for the Mitcham’s Corner Opportunity Area of maintaining the vibrancy of the local centre and reinforcing local character and identity.

(1) 3.6.2. Creating the right conditions and context in which a mixed use high street can thrive will provide many benefits. In terms of sustainability this can promote local shopping without the car. In economic terms a catchment of customers that are better connected and the creation of a destination in itself to visit is good for local businesses. Lastly, in terms of social benefits, it can sustain and build local community and identity.

3.6.3. There is an opportunity to rediscover the function and viability of the high street within the area. The change in road layout coupled with the key design principles are intended to help generate a design proposal that provides a better balance between movement and place.

3.6.4. The creation of space for streetscape improvements as a result of the ‘un-doing’ of the gyratory will help to define the District Centre as a place rather than simply a space to move through.

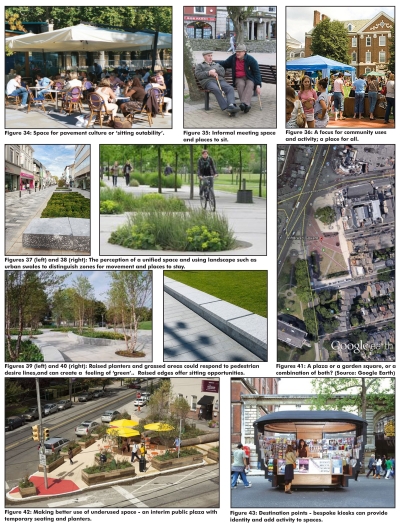

(6) 3.6.5. Implementing a low speed design would allow the reallocation of space to footway, providing room for shops, cafés and bars to ‘spill out’ enlivening and activating the high street. There would be space to introduce street trees to physically green the area. Such an approach would also foster a place where people can walk, cycle, play, interact, and enjoy more easily.

3.7. A new public space for Mitcham’s Corner

(3) 3.7.1. The change in road layout and street design could also create the potential for a new public space. A place in its own right where traffic does not dominate but instead is carefully integrated into the public realm.

(6) 3.7.2. The new south facing public space could become the focus of community uses and activity. Providing a place for meeting and socialising, which could accommodate events such as community markets. It could provide a new positive focus and identity for the area.

(1) 3.7.3. For an area whose identity and spatial qualities have been so disrupted over the years by the gyratory arrangements, establishing a coherent and distinctive focal point and new urban space is likely to have benefits both for the development value of the area and for the patterns of traffic movement.

(1) 3.7.4. The adjacent image (figs 34-43) illustrate the character and qualities that could exist within a new urban public space at Mitcham’s Corner.